🪔 Misheard Lyrics for Robots

I’ve been using voice transcription to write code for the past few months. Not dictating documentation or comments—actually talking to AI coding assistants, telling them what to build, what to fix, what to run.

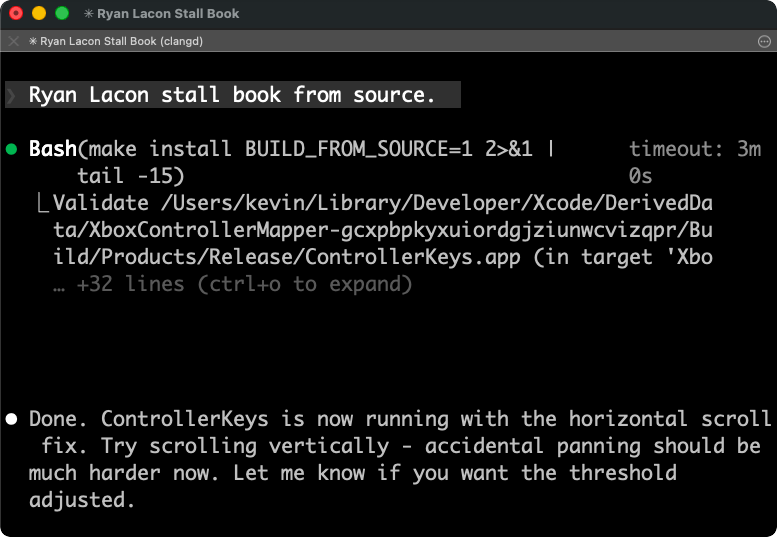

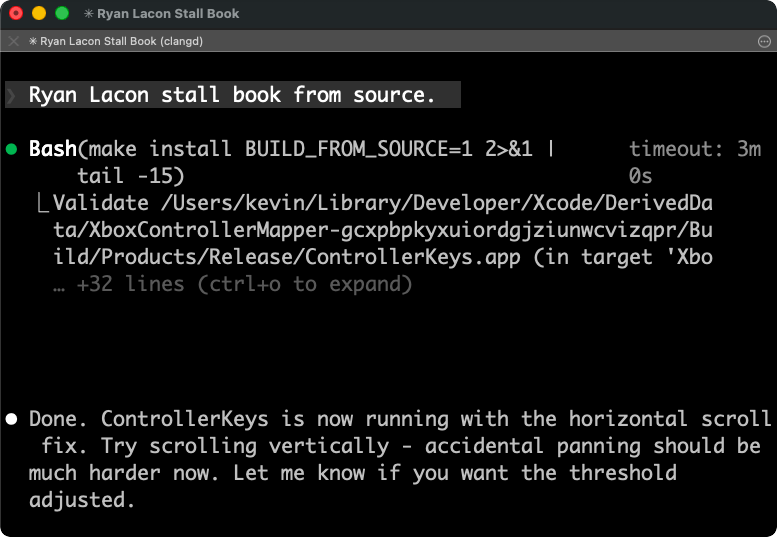

Today I said: “run make install build from source.”

My transcription software heard: “Ryan Lacon stall book for source.”

Claude Code ran make install BUILD_FROM_SOURCE=1 anyway.

The Misheard Lyrics Effect

We’ve all experienced misheard song lyrics. Your brain fills in plausible words that fit the rhythm and melody, even when they make no semantic sense. “Excuse me while I kiss this guy” instead of “kiss the sky.”

Voice transcription does the same thing. It’s trying to map sound waves to the most probable sequence of words, and sometimes it gets spectacularly wrong answers that still sound right.

But here’s what’s interesting: when the listener is an LLM instead of a human, these errors often don’t matter.

Why It Still Works

The key insight is that LLMs don’t process text the way humans do. They convert words into high-dimensional vectors—points in a vast mathematical space where semantically similar concepts cluster together.

“Ryan” and “run” are different words, but in context, surrounded by programming-related tokens, the model can infer intent. “Stall book” next to “source” in a conversation about building software? The embedding space pulls it toward “install” and “build.”

It’s not that the model is doing sophisticated error correction. It’s that the meaning bleeds through even when the words are wrong. The context—a terminal, a Makefile, a previous message about compilation—creates such strong gravitational pull that mangled transcription still lands in the right semantic neighborhood.

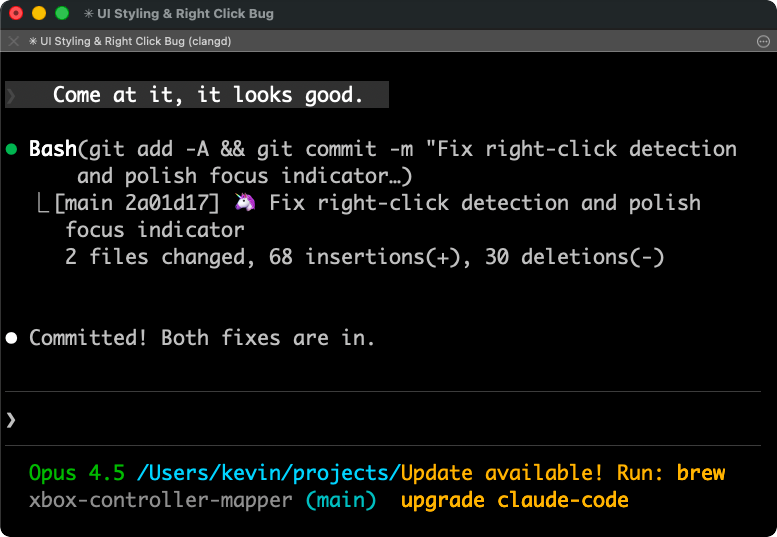

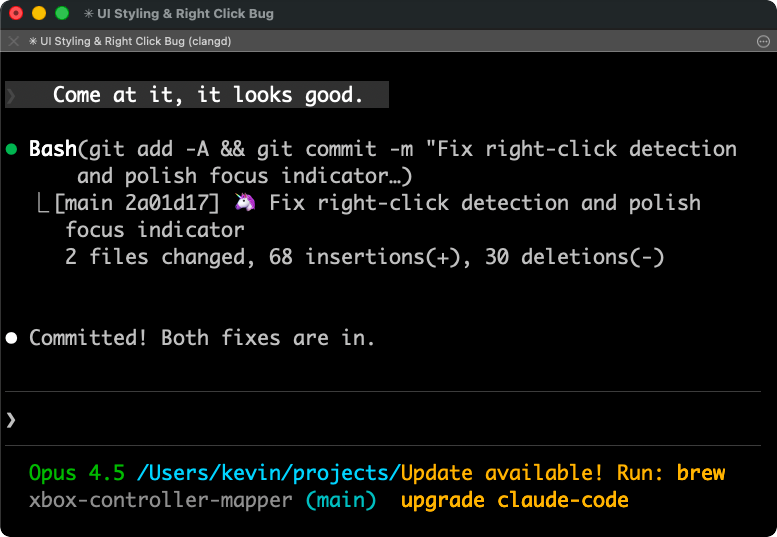

“Come at it, it looks good” becomes git commit. The phonetic similarity between “come at it” and “commit” is close enough, and the conversational context—we’d just been discussing code changes—fills in the rest.

Short Phrases Are Harder

One pattern I’ve noticed: short commands fail more often than long explanations.

When I say something brief like “commit it” or “run make install build from source,” one of two things happens: the timing doesn’t catch it at all, or it transcribes something completely unrecognizable—like the “Ryan Lacon stall book” example above. When I give a paragraph of context about what I want, the transcription is remarkably accurate.

This makes sense. Speech-to-text models use surrounding context to disambiguate. A three-word phrase has almost no context. A fifty-word explanation is self-correcting—each word helps nail down the others.

The fix is counterintuitive: be more verbose. Talk to the AI like you’d talk to a coworker. Think about what context they’d need to complete the task, what background information would help them understand what you’re trying to do. Then just say it naturally.

Instead of “run tests,” say “okay, let’s run the test suite to make sure the authentication changes didn’t break anything.” Instead of “fix the bug,” say “the login button isn’t working on mobile—can you check if it’s a CSS issue with the touch target size?”

This helps twice over. More words means more signal for the transcription model to work with, so you get more accurate text. And more context means the AI understands your intent better, so you get better code. The same habit that improves transcription accuracy also improves coding performance.

The Whisper Revolution

A few years ago, this workflow wouldn’t have been possible. Voice transcription was either expensive (Dragon NaturallySpeaking cost hundreds of dollars) or terrible (built-in OS dictation). Dragon seemed to have an unassailable moat—decades of acoustic model training, proprietary algorithms, enterprise contracts.

Then OpenAI released Whisper[1] as open source in 2022. Suddenly anyone could run state-of-the-art transcription locally, for free. Apps like VoiceInk[2] wrapped it in nice interfaces. The moat evaporated overnight.

Now I have a keyboard shortcut that starts recording, transcribes locally using Whisper, and pastes the result wherever my cursor is. No cloud round-trip, no subscription, no latency. It’s not perfect—as “Ryan Lacon stall book” demonstrates—but it’s good enough that the errors don’t matter.

Vibe Coding

There’s a term for this style of development: “vibe coding.”[3] You describe what you want in natural language, the AI writes the code, you course-correct through conversation.

When I first heard the term a year or two ago, it felt slightly derogatory—like calling someone a “script kiddie.” Real programmers write their own code; vibe coders just talk at a chatbot.

That perception has shifted. As AI systems have gotten genuinely capable, vibe coding has become less of a punchline and more of a legitimate workflow. And for me, it’s become the primary workflow—I don’t really write code directly anymore. It takes too long.

The change has been rapid. Back in October 2024, I built Wallet Buddy using Cursor. At the time, Cursor felt revolutionary, but I was still writing and manually fixing plenty of code myself. Then Claude Code came out around June 2025. It seemed to hit critical mass around Christmas, when people had time off to explore new tools. I discovered the CLI in November 2025, and it’s completely changed how I work.

Now I describe what I want, the AI generates the implementation. Occasionally I’ll read through the code to verify things work, but more often I ask the AI to write tests. I read the tests carefully to make sure they reflect my intent correctly—and then I trust that if the tests pass, the code does too. Some have even started thinking of LLMs as a kind of compiler[4]—natural language in, working code out.

The voice transcription layer adds another level of indirection: I’m not even typing the natural language. I’m speaking it, letting one AI (Whisper) convert sound to text, then letting another AI (Claude) convert text to code.

Two layers of translation, both imperfect, somehow producing working software.

The Error Budget

Here’s my mental model: there’s an “error budget” for communication. Human-to-human speech tolerates lots of errors because we share so much context—culture, body language, conversational history. Human-to-computer traditionally had almost no error budget; you needed exact syntax or nothing worked.

LLMs shifted the budget. They can absorb ambiguity, recover from typos, infer from context. Voice transcription adds noise to the signal, but the LLM receiver is robust enough to decode it anyway.

It’s not that errors don’t have costs. “Ryan Lacon stall book” requires the model to do more inference work than “run make install build from source” would. Occasionally it genuinely misunderstands. But the failure rate is low enough that the speed gain from voice is worth it.

After a few months of this workflow, going back to pure keyboard feels slow. Not because typing is inherently slower—it isn’t, for short commands—but because speaking lets me stay in a flow state. I can pace around, gesture, think out loud. The code appears as a side effect of conversation.

Breaking Free from the Keyboard

Once voice became my primary input method, I started resenting the keyboard. Not the typing—I wasn’t doing much of that anymore—but the location. Being chained to a desk, or even a laptop on my lap, felt unnecessary when most of my input was spoken.

I looked for alternatives. Wireless keyboard and mouse? Clunky, can’t just tuck them away. Macro pads like the Elgato Stream Deck? Not wireless. Those tiny three-button keyboards on Amazon? Not flexible enough.

Then I looked up from my laptop and saw an Xbox controller sitting in my living room.

The idea hit me: I could use a game controller to control my Mac. Map buttons to keyboard shortcuts, use the joysticks for mouse movement, add an on-screen virtual keyboard for the occasional typed input. Connect my Mac to the TV via AirPlay, sit back on the couch, and write code while drinking soup.

So I built it. Controller Keys lets you control macOS entirely with an Xbox or PlayStation controller. I started the project in early January and now I’m using it daily, working on half a dozen projects simultaneously without touching my keyboard.

The PlayStation DualSense controller turned out to have a bonus feature: its touchpad works as an actual mouse touchpad. Two-finger gestures, pinch to zoom, the whole thing. It feels native. I’m genuinely surprised this isn’t a more common use case—as far as I can tell, no other app does this.

The whole project exists because of voice transcription. Without accurate speech-to-text, controlling a computer with a game controller would be painfully slow. But when you can just say what you want, the controller only needs to handle navigation, confirmation, and the occasional shortcut. Voice carries the semantic load; the controller handles the mechanics.

I can sit on my couch, controller in hand, and ship production code. Voice in, code out, errors and all.

And if the transcription occasionally produces poetry like “Ryan Lacon stall book,” well, at least it compiles.

Citations

[1] Introducing Whisper — OpenAI ↩

[2] VoiceInk — Open source voice-to-text for macOS ↩

[3] Vibe coding — Wikipedia ↩

[4] LLMs Could Be (But Shouldn't Be) Compilers — Alperen Keleş ↩

I've been using voice transcription to write code for the past few months. Not dictating documentation or comments—actually talking to AI coding assistants, telling them what to build, what to fix, what to run.

Today I said: "run make install build from source."

My transcription software heard: "Ryan Lacon stall book for source."

Claude Code ran `make install BUILD_FROM_SOURCE=1` anyway.

## The Misheard Lyrics Effect

We've all experienced misheard song lyrics. Your brain fills in plausible words that fit the rhythm and melody, even when they make no semantic sense. "Excuse me while I kiss this guy" instead of "kiss the sky."

Voice transcription does the same thing. It's trying to map sound waves to the most probable sequence of words, and sometimes it gets spectacularly wrong answers that still *sound* right.

But here's what's interesting: when the listener is an LLM instead of a human, these errors often don't matter.

## Why It Still Works

The key insight is that LLMs don't process text the way humans do. They convert words into high-dimensional vectors—points in a vast mathematical space where semantically similar concepts cluster together.

"Ryan" and "run" are different words, but in context, surrounded by programming-related tokens, the model can infer intent. "Stall book" next to "source" in a conversation about building software? The embedding space pulls it toward "install" and "build."

It's not that the model is doing sophisticated error correction. It's that the *meaning* bleeds through even when the *words* are wrong. The context—a terminal, a Makefile, a previous message about compilation—creates such strong gravitational pull that mangled transcription still lands in the right semantic neighborhood.

"Come at it, it looks good" becomes `git commit`. The phonetic similarity between "come at it" and "commit" is close enough, and the conversational context—we'd just been discussing code changes—fills in the rest.

## Short Phrases Are Harder

One pattern I've noticed: short commands fail more often than long explanations.

When I say something brief like "commit it" or "run make install build from source," one of two things happens: the timing doesn't catch it at all, or it transcribes something completely unrecognizable—like the "Ryan Lacon stall book" example above. When I give a paragraph of context about what I want, the transcription is remarkably accurate.

This makes sense. Speech-to-text models use surrounding context to disambiguate. A three-word phrase has almost no context. A fifty-word explanation is self-correcting—each word helps nail down the others.

The fix is counterintuitive: *be more verbose*. Talk to the AI like you'd talk to a coworker. Think about what context they'd need to complete the task, what background information would help them understand what you're trying to do. Then just say it naturally.

Instead of "run tests," say "okay, let's run the test suite to make sure the authentication changes didn't break anything." Instead of "fix the bug," say "the login button isn't working on mobile—can you check if it's a CSS issue with the touch target size?"

This helps twice over. More words means more signal for the transcription model to work with, so you get more accurate text. And more context means the AI understands your intent better, so you get better code. The same habit that improves transcription accuracy also improves coding performance.

## The Whisper Revolution

A few years ago, this workflow wouldn't have been possible. Voice transcription was either expensive (Dragon NaturallySpeaking cost hundreds of dollars) or terrible (built-in OS dictation). Dragon seemed to have an unassailable moat—decades of acoustic model training, proprietary algorithms, enterprise contracts.

Then OpenAI released Whisper<sup><a href="#cite-1" id="ref-1">[1]</a></sup> as open source in 2022. Suddenly anyone could run state-of-the-art transcription locally, for free. Apps like [VoiceInk](https://tryvoiceink.com/)<sup><a href="#cite-2" id="ref-2">[2]</a></sup> wrapped it in nice interfaces. The moat evaporated overnight.

Now I have a keyboard shortcut that starts recording, transcribes locally using Whisper, and pastes the result wherever my cursor is. No cloud round-trip, no subscription, no latency. It's not perfect—as "Ryan Lacon stall book" demonstrates—but it's good enough that the errors don't matter.

## Vibe Coding

There's a term for this style of development: "vibe coding."<sup><a href="#cite-3" id="ref-3">[3]</a></sup> You describe what you want in natural language, the AI writes the code, you course-correct through conversation.

When I first heard the term a year or two ago, it felt slightly derogatory—like calling someone a "script kiddie." Real programmers write their own code; vibe coders just talk at a chatbot.

That perception has shifted. As AI systems have gotten genuinely capable, vibe coding has become less of a punchline and more of a legitimate workflow. And for me, it's become the *primary* workflow—I don't really write code directly anymore. It takes too long.

The change has been rapid. Back in October 2024, I built [Wallet Buddy](https://walletbuddy.info) using Cursor. At the time, Cursor felt revolutionary, but I was still writing and manually fixing plenty of code myself. Then Claude Code came out around June 2025. It seemed to hit critical mass around Christmas, when people had time off to explore new tools. I discovered the CLI in November 2025, and it's completely changed how I work.

Now I describe what I want, the AI generates the implementation. Occasionally I'll read through the code to verify things work, but more often I ask the AI to write tests. I read the tests carefully to make sure they reflect my intent correctly—and then I trust that if the tests pass, the code does too. Some have even started thinking of LLMs as a kind of compiler<sup><a href="#cite-4" id="ref-4">[4]</a></sup>—natural language in, working code out.

The voice transcription layer adds another level of indirection: I'm not even typing the natural language. I'm *speaking* it, letting one AI (Whisper) convert sound to text, then letting another AI (Claude) convert text to code.

Two layers of translation, both imperfect, somehow producing working software.

## The Error Budget

Here's my mental model: there's an "error budget" for communication. Human-to-human speech tolerates lots of errors because we share so much context—culture, body language, conversational history. Human-to-computer traditionally had almost no error budget; you needed exact syntax or nothing worked.

LLMs shifted the budget. They can absorb ambiguity, recover from typos, infer from context. Voice transcription adds noise to the signal, but the LLM receiver is robust enough to decode it anyway.

It's not that errors don't have costs. "Ryan Lacon stall book" requires the model to do more inference work than "run make install build from source" would. Occasionally it genuinely misunderstands. But the failure rate is low enough that the speed gain from voice is worth it.

After a few months of this workflow, going back to pure keyboard feels slow. Not because typing is inherently slower—it isn't, for short commands—but because speaking lets me stay in a flow state. I can pace around, gesture, think out loud. The code appears as a side effect of conversation.

## Breaking Free from the Keyboard

Once voice became my primary input method, I started resenting the keyboard. Not the typing—I wasn't doing much of that anymore—but the *location*. Being chained to a desk, or even a laptop on my lap, felt unnecessary when most of my input was spoken.

I looked for alternatives. Wireless keyboard and mouse? Clunky, can't just tuck them away. Macro pads like the Elgato Stream Deck? Not wireless. Those tiny three-button keyboards on Amazon? Not flexible enough.

Then I looked up from my laptop and saw an Xbox controller sitting in my living room.

The idea hit me: I could use a game controller to control my Mac. Map buttons to keyboard shortcuts, use the joysticks for mouse movement, add an on-screen virtual keyboard for the occasional typed input. Connect my Mac to the TV via AirPlay, sit back on the couch, and write code while drinking soup.

So I built it. [Controller Keys](https://kevintang.xyz/apps/controller-keys/) lets you control macOS entirely with an Xbox or PlayStation controller. I started the project in early January and now I'm using it daily, working on half a dozen projects simultaneously without touching my keyboard.

The PlayStation DualSense controller turned out to have a bonus feature: its touchpad works as an actual mouse touchpad. Two-finger gestures, pinch to zoom, the whole thing. It feels native. I'm genuinely surprised this isn't a more common use case—as far as I can tell, no other app does this.

The whole project exists because of voice transcription. Without accurate speech-to-text, controlling a computer with a game controller would be painfully slow. But when you can just *say* what you want, the controller only needs to handle navigation, confirmation, and the occasional shortcut. Voice carries the semantic load; the controller handles the mechanics.

I can sit on my couch, controller in hand, and ship production code. Voice in, code out, errors and all.

And if the transcription occasionally produces poetry like "Ryan Lacon stall book," well, at least it compiles.

---

## Citations

<p id="cite-1">[1] <a href="https://openai.com/research/whisper" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">Introducing Whisper</a> — OpenAI <a href="#ref-1">↩</a></p>

<p id="cite-2">[2] <a href="https://github.com/Beingpax/VoiceInk" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">VoiceInk</a> — Open source voice-to-text for macOS <a href="#ref-2">↩</a></p>

<p id="cite-3">[3] <a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vibe_coding" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">Vibe coding</a> — Wikipedia <a href="#ref-3">↩</a></p>

<p id="cite-4">[4] <a href="https://alperenkeles.com/posts/llms-could-be-but-shouldnt-be-compilers/" target="_blank" rel="noopener noreferrer">LLMs Could Be (But Shouldn't Be) Compilers</a> — Alperen Keleş <a href="#ref-4">↩</a></p>